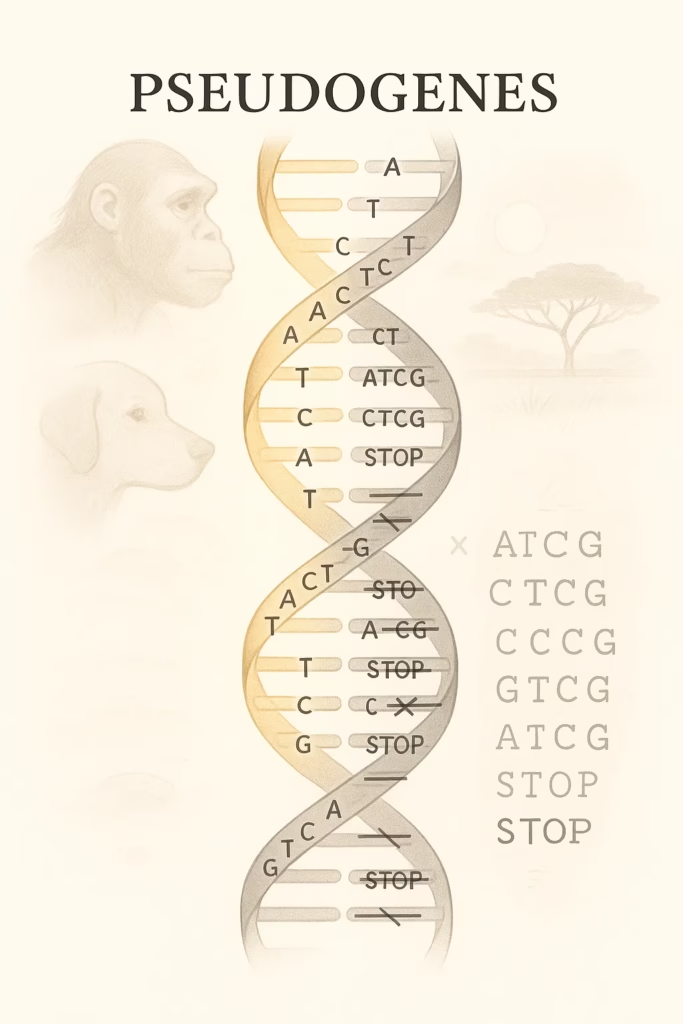

Introduction: The Genomic Library of Unusable Code 📚

Imagine you’re reviewing a software’s source code and you find huge sections of commented-out code, functions that are never called, and even parts with obvious syntax errors that prevent them from being compiled. An entire library of useless programs. Why would anyone keep this? This is exactly what happens in our DNA. Roughly half of our genes are “healthy,” while the other half is a collection of pseudogenes – “dead” genes that have lost their ability to produce functional proteins due to mutations (insertions, deletions, misplaced stop codons). They are not just genetic ballast; they are the fossil record of our evolutionary adventures.

Why Are They Inherited? Energy Inefficiency or Genetic Thrift? 💰

Is it pointless for an organism to spend energy replicating this “dead” code? It turns out that the cost of maintaining pseudogenes is extremely low. DNA replication is such an efficient process that the burden of copying a few thousand extra base pairs is negligible compared to the potential benefits or even the simple inertia of these sequences.

Evolution does not remove them for the same reason you don’t clean every speck of dust the moment it appears in a room – the cost of cleaning is often greater than the usefulness of the space the dust occupies. As long as a pseudogene isn’t harmful, there is no natural selection pressure to eliminate it.

The Stories Pseudogenes Tell: How We Became Who We Are 📖

Each pseudogene is like a chapter from a lost book about our ancestors.

The Story of Lost Self-Sufficiency: Vitamin C 🍊

- Fact: Humans, apes, and our humanoid ancestors cannot synthesize vitamin C (ascorbic acid), unlike most other mammals.

- Genetic Evidence: We have the gene for the key enzyme required for this task (L-gulonolactone oxidase), but in us, it is a pseudogene (labeled GULOP). A mutation introduced a stop codon that interrupts protein synthesis.

- Evolutionary Lesson: Our ancestors were herbivores with a diet rich in vitamin C (fruit, leaves). In such an environment, the ability for self-synthesis provided no advantage, so the mutation that “switched off” the gene spread through the population without harmful consequences. This is a classic example of genetic thrift – why waste energy producing something that is already available in abundance?

The Story of Changing Senses: The Lost World of Smell 👃

- Fact: Dogs can detect smells at concentrations up to 100 million times lower than humans can.

- Genetic Evidence: We have about 400 functional genes for smell receptors, but over 600 pseudogenes. This means that more than 60% of our “olfactory genome” is non-functional.

- Evolutionary Lesson: As our ancestors transitioned to a diurnal lifestyle and became increasingly dependent on sight and hearing for communication and hunting, the olfactory system became less critical. The selective pressure to maintain every single smell receptor decreased, allowing many of them to become “corrupted” and turn into pseudogenes. Our brain then restructured itself, giving priority to the visual and auditory cortices.

The Story of Lost Protection: Thick Skin and Vitamin D ☀️

- Fact: Most mammals have thick fur. Humans are one of the few “naked” mammals.

- Genetic Evidence: There are pseudogenes for certain types of keratin (a hair protein), indicating the loss of various hair types during our evolution.

- Evolutionary Lesson: The loss of fur can be linked to the need for thermoregulation during hunting in the savannah—specifically, for more efficient heat dissipation. Furthermore, there is also a direct connection with vitamin D. Without thick fur blocking the sun’s rays, human skin became more efficient at producing vitamin D under the strong African sun.

Is This a Strategy for the Future? A “Genetic Reserve” 🔮

Although the complete reactivation of a pseudogene into a functional gene is extremely rare (because it’s much easier to create a new error than to fix a series of old ones), pseudogenes are not entirely useless. They serve as:

- Raw Material for Evolution: Pseudogenes can be duplicated, recombined, and serve as “raw material” for the emergence of completely new genes over time. This is the genomic equivalent of recycling.

- Regulatory Elements: Some pseudogenes produce RNA molecules that can regulate their functional “cousins,” acting as “decoys” for regulatory proteins.

- Genetic Resilience: Although reactivation is rare, there is a possibility that pseudogenes preserve genetic diversity. If the environment changes dramatically, organisms with partially “repaired” pseudogenes (via a rare mutation) could regain a lost advantage.

Conclusion

Pseudogenes are not a shameful mark of failure in our genome. They are proof of adaptability and compromise. Each one carries a story about a change in the diet, environment, behavior, or social structure of our ancestors. They are proof that evolution often does not add new functionalities, but takes away what is no longer needed, saving energy and redirecting resources toward what is necessary. By studying these genomic “fossils,” we not only understand what we have lost but also why we became exactly what we are – beings dependent on vitamin C, with an inferior sense of smell, but with a powerful brain capable of deciphering their secrets.

Leave a Reply