Did Kepler’s laws—the foundation of Newtonian physics—emerge as a byproduct of the search for the perfect horoscope? 🔮🪐➡️📐🚀

In today’s sharply divided world, astrology and astronomy stand on opposite sides—one considered a pseudoscience, the other a rigorous discipline.

But history reveals a far more intricate, symbiotic relationship. At a time when no sharp boundary existed, it was precisely astrology’s need for accuracy that sparked some of the greatest discoveries in the history of science.

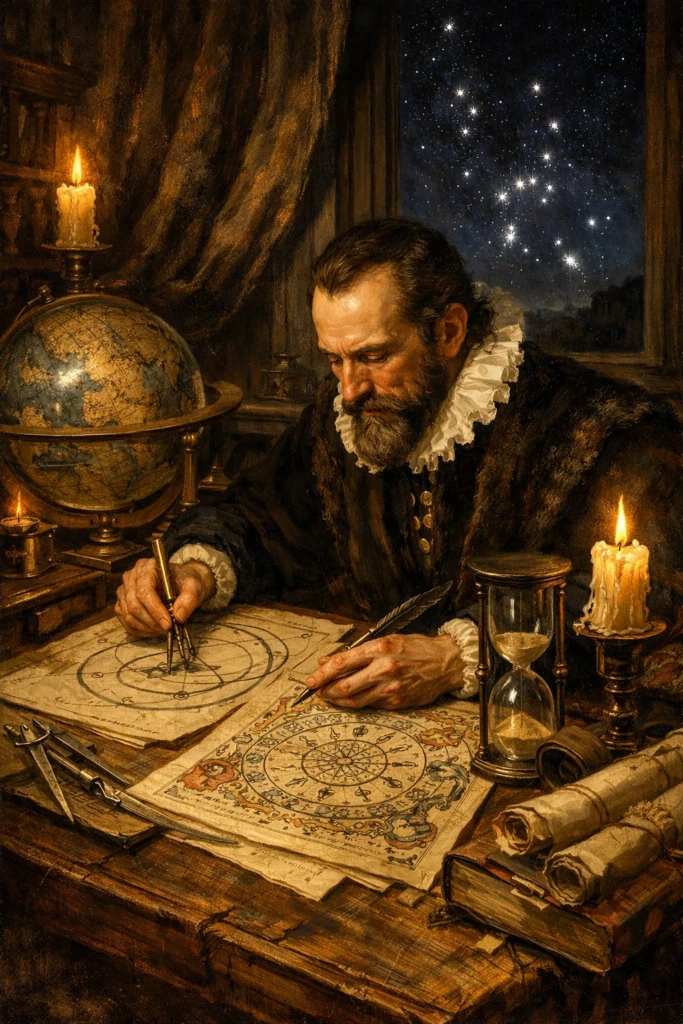

Johannes Kepler: Astrologer in the Service of Science (or Vice Versa?) 🧑🔬✨

Kepler is now described as the father of celestial mechanics, the man who uncovered the elliptical orbits of planets.

But less is said about astrology being his primary source of income. He served as the official astrologer in Graz and later for Emperor Rudolf II in Prague.

At that time, horary astrology was crucial for rulers and nobles. Unlike today’s focus on natal horoscopes (which were rare then due to unknown exact birth times), horary astrology provides precise answers to specific questions by interpreting a chart cast for the exact moment and place a question is asked.

Kepler’s motivation was not purely curiosity. He was financially compelled to improve astronomical predictions. His desire to “forecast fate” paradoxically led to discoveries that shook the astrological view of the universe.

The Theft That Changed the Cosmos: Tycho Brahe and His “Stolen” Data 🌌📊

Tycho Brahe, the eccentric Danish astronomer, possessed the most precise observational data of his time—measurements of Mars’ position with an error of just 2 arcminutes.

Upon Brahe’s death in 1601, Kepler (as his assistant) took over—or according to some sources, stole—these priceless records.

This controversial fact hides the essence: without Tycho’s accurate measurements, Kepler could not have discovered his laws. The data were crucial to reveal that Mars does not move in a perfect circle.

From Horoscope to Ellipse: Geometry as the Key 📐➡️🪐

With this data in hand, Kepler spent years trying to describe Mars’ orbit using traditional geometric shapes.

He used triangulation and relentless testing of mathematical models. When he finally accepted the ellipse (a shape ancient astronomers had dismissed as “imperfect”), he opened the door to modern science:

- First law: Planets move in elliptical orbits.

- Second law: The line connecting a planet to the Sun sweeps out equal areas in equal times (constancy of sectoral velocity).

- Third law: The square of the orbital period is proportional to the cube of the semi-major axis of the orbit.

These laws were not merely descriptive—they were quantitative, predictive. They enabled accurate forecasts of celestial motion independent of their alleged “influence” on human destinies.

Endless Irony: Astrology Gave Birth to the Science That Reshaped It 🔄⚖️

Kepler continued writing horoscopes and believing in some astrological concepts (like the “music of the spheres”) until the end of his life.

Yet his laws laid the groundwork for Newton’s theory of universal gravitation, which explained planetary motion through physical forces, not divine or astrological principles.

The greatest irony: The quest for accurate horoscopes for noble patrons led to discoveries that demystified the heavens and placed the universe under the rule of mathematical laws—laws that narrow the space for traditional astrological interpretation.

The Bigger Picture: The Symbiosis of Science and Pseudoscience Throughout History 📜🔄

This story is not isolated. Alchemy led to chemistry (even the great Isaac Newton practiced alchemy, numerology, and attempts to decode biblical cyphers).

Some folk healing and herbal practices paved the way for modern medicines and therapies. Trepanation of the skull can be viewed as the beginning of neurosurgery.

It reminds us that scientific progress often arises from impure motives—economic, religious, even mystical.

Food for thought: Would Kepler have reached his discoveries without the financial pressure to cast horoscopes? Is the need for applied knowledge (even if mistaken) often a stronger driver than pure theoretical curiosity?

This topic is a perfect example of how the history of science often breaks down our simple divisions.

What do you think: Was the relationship between astrology and astronomy a necessary symbiosis or a fortunate accident? Are there similar examples today—where “pseudoscience” or practical needs hide behind progress?

Leave a Reply